B. Udine 1699, d. after 1758

Sanctus Seraphin (or Santo Seraphino) somehow stands apart from the other makers of Venice. In 1740 he was probably the most prolific and commercially successful maker in the city, at a time when the competition included the likes of Domenico Montagnana and Pietro Guarneri. In fact, in 1744 he was persuaded by the guild of instrument makers to stop production. What differentiates him from his peers in Venice is his consistency of style and his precise and slightly mannered workmanship. A definition of Venetian violin making would usually describe a looseness of style, an improvisatory approach and a wide range of patterns and models, often appropriated from other sources. Seraphin represents the polar opposite of these qualities. The richness of instrument making in Venice derived largely from the fact that virtually all it's luthiers came from outside the city, and brought with them different techniques and approaches to the craft. Seraphin too was strictly speaking an outsider, born in Udine, but whether or not he brought any fresh experience of instrument making with him to Venice is difficult to say. While Udine is not far outside Venice, Seraphin was twenty before he came to the city from his home town, and it seems unlikely that he was without a trade during that time. But no more than five years after arriving in Venice in around 1720 he was labelling his own instruments, and within another five years had formed his own characteristic style. Udine was home to more than it's fair share of makers. Francesco Gobetti, another outstanding Venetian maker, was born there in 1675, and Matteo Gofriller's son Francesco moved there in 1714, when Seraphin was just fifteen and still resident in the town.

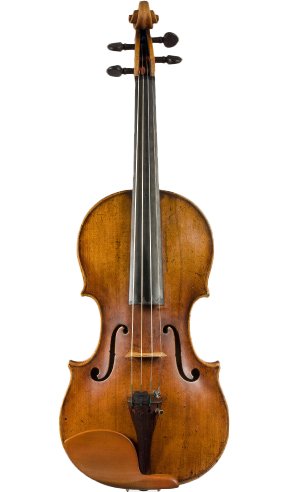

Seraphin's style is ultimately a personalised Amati model, built on the classical proportions, but with slightly exaggerated archings. These can be quite high, and dramatically scooped around the edges, admittedly not far removed from some of Nicolo Amati's braver experiments. The fashion for Stainer's work had penetrated Venice in this period, and there was an obvious taste for the sweet, chamber sound that this sort of arch provides. Seraphin was not drawn by the fashion for the cello in Venice however. While Gofriller and Montagnana are revered today for their cellos, which are both fabulous in tone and comparitively plentiful, few of Seraphin's surviving instruments are larger than a violin.

One of the interesting traits of Seraphin's workmanship is his habit of carving the corners thinner than the rest of the edge. This is in contrast to the almost universally adopted practice of leaving the corners and button thicker, giving them a noticeably flared appearance when viewed side-on. Whether this was done for purely visual, aesthetic purposes, a precaution against the excessive wear to which the corners are exposed, or was an inevitable result of the working process is debated. Whatever the reason, Seraphin approached it differently. So did J.B.Guadagnini, but there is no other connection that can be drawn between the two very different makers. In other ways, Seraphin's craftsmanship is elegant to a fault, with long corners and neatly mitred purflings, and beautifully cut soundholes. His scroll is very distinctive, and has slightly odd proportions, generally with a rather deep pegbox surmounted by a small, tightly coiled scroll. The last turn generally travels a bit further than usual, terminating behind rather than beneath the eye. Perhaps the best known 'trademark' of Seraphin is the small half-circle which appears in the end of the pegbox mortice. It is invariably present in his heads, and perhaps results from a drilled hole made to mark the end and depth of the mortice, which was then worked up to with the chisel used to chase out inside of the pegbox.

Seraphin was not shy about advertising his name. The very personal touches he brought to his work were not enough. He generally used a large brand with which he burnt his name onto the lower ribs between the endpin and saddle, and a particularly ornate label within the instrument, although this is a general trait of makers in Venice, where the craft of printing was at a zenith of sophistication. It is hard not to think of Seraphin as a driven, headstrong man, with more than a touch of the flamboyant in his character. He applied his varnish with relish too, although perhaps with more care than others. You seldom see the intense crackling in the surface that almost defines Montagnana's work, yet his colours can be as intensely soaked in red. What is more normal with Seraphin however is a more subtle, evenly applied golden brown .

Seraphin left no sons, but his nephew Giorgio was presumably trained by him, and became a very distinctive and often inspired maker in his own right. He seems to have left his uncle's workshop in the early 1740s to establish his own business, and ultimately to take over that of Domenico Montagnana, his father-in-law. Giorgio's work has little of the discipline of Sanctus', although the lineage from two of Venice's greatest makers is clear. It is a shame that his instruments, in contrast with those of his uncle, are so frustratingly rare.