Orville H. Gibson (1856-1918) was born of an American mother and an English father near Chateaugay, close to the Canadian border in northern New York state. (No local registrars' records survive from the year of his birth, and it is not known what his middle initial stood for.) During his childhood, he developed considerable skills as a wood-carver, as well as a strong interest in music; and as a young man, he moved to Kalamazoo in southwestern Michigan, where, from the mid-1880s, he held various clerical posts while pursuing a passion for instrument building.

His early creations included a number of violins; and the mandolins for which he is better known had violin-like, arched soundboards (rather than flat or bent tops) and partially hollowed-out necks. In a patent application filed in May 1895 and granted in February 1898, he explained that his mandolins' sides, necks and heads were "carved out of a single piece of wood", and that this, as well as the shaping of their tops and backs "in a somewhat convex form...preferably thickest at and near the center", helped to produce "a character and quality of sound entirely new to this class of musical instruments."

Orville's guitars had similar features: carved, arched tops and oval, 'Neapolitan-style' soundholes. During construction, their fronts and backs were 'tuned' (to optimise their resonating properties) by a painstaking process of tapping and carving similar to the techniques of European violin-builders. Many of the guitars also boasted additional strings mounted in 'harp-style' configurations, and were considerably larger than models by any contemporary luthiers.

On 11th October 1902, Orville Gibson entered into an agreement with five Kalamazoo businessmen that resulted in the formation of the Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Manufacturing Company. Surprisingly, Orville was not a partner in the firm, although he received a fee for allowing it to use his patented designs. In fact, his direct involvement with the enterprise bearing his name was relatively brief - perhaps as a consequence of his poor health, which led to his departure from Kalamazoo in 1909. He died of heart disease at Ogdensberg, NY on 21st August 1918, about a year before the Gibson company recruited Lloyd Loar - the brilliant young technician who would take its archtop mandolins and guitars to new levels of sophistication and excellence.

Prior to Loar's arrival, the mainstay of Gibson's guitar range was its 'L' series. Four 'L' models were listed in its 1902 catalogue: the 'Style L' (quickly discontinued); the L-2 (which survived until 1908, and was made in three sizes); and the longer-lived L-1 and L-3, joined in 1911 by the larger L-4.

Like Orville Gibson's earlier designs, the early 'Ls' were arch-topped and steel-strung; but in other ways, they differed substantially from them. They lacked the elaborate inlays that Orville had favoured, and were much smaller than his 'harp-guitars', some of which had been up to 21 inches (53.3cm) wide; the L-1 and L-3 had a modest 13.5-inch (34.3cm) body width, while the L-4 was a 16-inch (40.6cm) model. The 'L' series also failed to implement some of Orville's ingenious ideas about internal construction, such as his method of building an instrument's sides and neck from a single piece of wood.

By the end of World War I, though, other important new techniques were being developed at Gibson. One of its employees, Ted McHugh, was responsible for introducing the truss-rod - a steel bar, fitted inside the neck, which greatly improved the guitar's strength and rigidity, and allowed the neck itself to be made slimmer and more comfortable for the player. Truss-rods were fitted as standard to most Gibson guitars from 1922 onwards; but the firm's most dramatic design breakthroughs were displayed by the L-5, which set the standard for all subsequent archtop guitars, and was the brainchild of its chief instrument designer, Lloyd Loar.

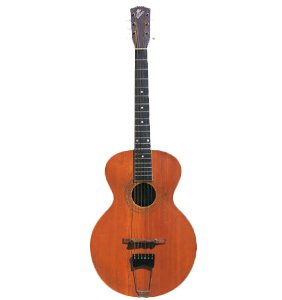

GIBSON L-1, c.1920

A late example of an archtop design first produced by Gibson in 1902. Its distinctive headstock logo (which can also be seen on the L-4) was used on most Gibsons until the mid-1920s; earlier, "Orville-style" instruments featured a star and crescent inlay.

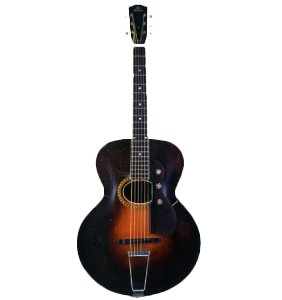

GIBSON L-4, c.1924

The L-4 was introduced in 1912, and remained in production until 1956. This guitar belongs to the leading British jazz player Martin Taylor; other distinguished L-4 users have included Ry Cooder.

Lloyd Allayre Loar (1886-1943) possessed an unusual range of talents. He was a music graduate and a skilled mandolinist and viola player, as well as an engineer with a keen grasp of the technical aspects of instrument design. During his five-year stay at Gibson (1919-1924), he was responsible for product development, improving existing models and experimenting with new concepts, including electric guitars. But his great contribution to the evolution of the acoustic instrument was his work on the Gibson L-5, which first appeared in 1922 and is now recognised as one of the most important and influential archtops ever built.

Like Orville Gibson, Loar made his first breakthroughs in mandolin design, and then applied them to guitar construction. In 1922, he introduced the Gibson F-5, a mandolin that took Orville's arched top a stage closer to its violinistic origins by using f-holes in place of the instrument's customary oval soundhole. Later that year, the L-5 guitar appeared; it, too, had f-holes, as well as other novel features: a truss-rod, an adjustable bridge, and a system of top-bracing that used two parallel wooden bars glued to the inside of the soundboard. The result was a guitar with a winning combination of playability, tone-quality, and power, which was taken up by a number of influential American players - notably Eddie Lang (1902-1933), whose recordings with fellow-guitarist Lonnie Johnson (1889-1970), and collaborations with violinist Joe Venuti (1903-1978) helped to establish the guitar as a solo instrument in jazz.

Gibson responded to the resultant demand by bringing out three other 'L' series archtops; the first of these, the L-10, was officially launched in 1931. It bore a strong resemblance to the L-5, but was not designed by Lloyd Loar, who had left the firm in 1924 after it refused to back his plans to produce electric instruments. He continued to develop his radical ideas until the war years, setting up his own company, Vivi-Tone, with two other ex-Gibson employees in 1933. It made guitars, mandolins and (later) an electric keyboard, but enjoyed little commercial success; and Gibson itself produced no electric models until 1936.

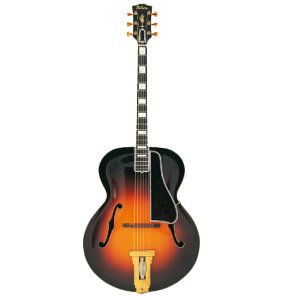

GIBSON L-5, 1937

The L-5 has a 17-inch (43.2cm) body, a two-piece spruce top, back and sides of maple, and an ebony-faced fingerboard with mother-of-pearl inlays. The 'flowerpot' logo on the headstock is found on many early Gibsons, but the pickguard fitted to this instrument is probably a later replacement.

GIBSON L-10, 1928

This L-10 was made three years before the model's official introduction, and is in near-mint condition; its glossy black finish has never been retouched. Its headstock, tuners and neck are all similar to the L-5's, although its ebony fingerboard has dot position markers rather than block inlays. The bridge is also ebony; on later L-10s, both bridge and fingerboard were made of rosewood. The tailpiece, with its visible slots for the strings, is a prototype design that was not used on production models.

VIVI-TONE GUITAR, 1933

Lloyd Loar's Vivi-Tone was in production for less than a year. The vibrations of its strings are passed from its bridge, via two steel screws, to a steel plate (clamped at one end and floating on the other) with a magnetic pickup mounted below it in a drawer-like compartment. The guitar's top has no sound-holes, but its back has small f-holes, and is recessed about half an inch (1.27cm) into the body.