It sometimes seems impossible to imagine life in seventeenth century Cremona. From our perspective, it appears to have been teeming with violin makers, with the whole town devoted to an almost mystical process of crafting these wonderful and timeless artefacts. In truth, it was not like that at all. Until the end of the century, there was only one significant violin workshop in the whole town as far as we can see, that of the Amati family. While Cremona was already celebrated for its music and musical instruments, and Cremonese musicians operated in aristicratic courts throughout Europe, making violins was by no means the focus of the whole city.

The real growth of the craft began slowly around 1640, when Nicolo Amati started training apprentices in his shop, and it is often assumed that Francesco Rugeri and Antonio Stradivari were amongst this elite. Again, the truth is not so clear. Many of Amati's pupils were quite undistinguished craftsmen who remain in deserved obscurity, and there is no actual evidence to show that Stradivari and Rugeri were ever there.

This may be only a theoretical objection; most of the Amati workmen we know about were not Cremonese in origin, and so they were recorded in the various censuses as resident in the Amati house. Stradivari and Rugeri were Cremonese, and resided elsewhere in the city, and maybe it is for that reason alone that they have no recorded connection with Nicolo Amati. On the face of it, again from superficial impressions, their work is so similar to that of Nicolo it is hard to imagine that they were not diligent pupils of the master, copying every line and stylistic affectation. But there are odd dissimilarities as well.

There are good reasons to view Francesco Rugeri and Antonio Stradivari as allies in some way, outside the circle of Amati. For one, again apparently minor detail, neither of these makers made use of the small pin found in the centre of the interior surface of the back which appears in all other Cremonese work, and in instruments made elsewhere by makers with a direct and traceable connection to the Amati family.

Francesco Rugeri was born around 1620, but his labelled instruments do not start to appear until 1670. There is no precise explanation for his occupation in the first fifty years of his life, and so it has always been assumed that most of his adulthood was spent with Amati. But another theory goes that he was busy making copies of Amati's instruments, one of which came to light in 1685, when a citizen of Modena complained that the violin he had bought as an Amati in fact turned out to have a Rugeri label beneath a false Amati ticket.

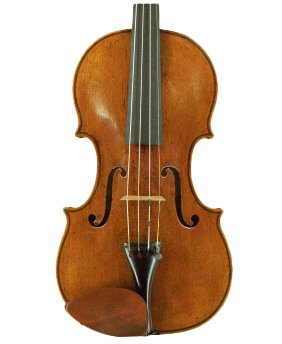

Rugeri's instruments are beautifully crafted. It takes a long hard look to distinguish them from Amatis, and the differences come down to minor details of the cut of the purfling and F holes, but mainly in the carving of the scroll. But it is still possible to see that Rugeri could have acquired many of the techniques of violin making without spending thirty years in obscurity in the Amati shop. It is not hard to copy an outline, trace the elements of the exterior work and buy varnish from the same pharmacist or colourman. But without that single pin in the centre of the back, it has to be said that Rugeri (and Stradivari for that matter) worked in a significantly different way to his supposed master.

Rugeri's scrolls are quite distinctive. Although usually very concentric and well balanced, they often show a pronounced ovality. The chamfer is usually very light, and the undercutting around the volute very flat around the first turn. The purfling is broad and well crafted, but quite often made of maple rather than the poplar wood universally used elsewhere in Cremona. His violin model is interesting in that it is pretty much invariably based on Nicolo Amati's Grand pattern, the broader version of the earlier Amati form which Nicolo introduced in about 1630. The very first violins made by Stradivari from 1666-1670, are by contrast made on the earlier narrow Amati model.

Stradivari was the younger man, born some fourteen years after Rugeri, but it seems indicative of some change in the working environment of Cremona that their instruments appear about the same time, among the very first Cremonese violins without an Amati label.

Rugeri's most important contribution nowadays is his magnificent cellos. Again, faithful copies of Amati, they differ in the one important aspect of size. They are, alongside Andrea Guarneri's instruments, the first Cremonese cellos made on what is now the accepted 29½ back length, and therefore of great importance and usefulness. All Amati cellos are or were quite massive and fairly unmanageable for modern players unless severely cut down in size. Curiously, Stradivari continued to make very large cellos until 1710, but the Rugeris dating from the 1680s are to all intents the prototypes of the modern instrument. Rugeri was quite prolific in their manufacture too- his cellos seem to be more common than any other Cremonese maker. While some are quite sumptuous in varnish and wood, others are made from plain cuts of poplar wood, with a thinner, duller coloured coating. neither are they entirely uniform in size. It is not certain whether the length was reduced gradually over time, or that various sizes were made contemporaneously, but there seems to have been a trend downwards towards the smaller size which appears in Rugeri's perfected form at the end of the seventeenth century. There certainly seems to be two sizes of head, a quite massive form belonging to the larger patterns, and a smaller form appropriate to the 29½ instrument. Both have the characteristic Rugeri features of the flat undercut at the first turn, and the very delicate chamfer.

Francesco Rugeri gave his nick-name 'Il Per' on his labels. Rugeri was and remains a common name in Cremona in all it's variant spellings, and we know that Giovanni Battista Rogeri was a pupil of Amati when Francesco was active. Francesco was obviously keen to discriminate himself, but the same cannot be said for his family.

There were several other violin makers of the Rugeri clan, most of whom have mysteriously almost disappeared from sight. Francesco had three sons, the eldest of whom was Giovanni Battista, who was born in 1653. What he did remains obscure. His own labels are particularly rare despite the fact that he must have made his living as a maker. The assumption must be that he assisted his father for most of his life, but retired shortly after Francesco's death in 1698. Giovanni Battista himself died in 1711. Francesco's second son was Giacinto (1661-1697) who also left a very few labelled instruments, which are relatively weak in style and workmanship. The youngest brother Vincenzo (1663-1719) was slightly more prolific, perhaps naturally so given that he survived his father rather longer than the other brothers. His work is interesting in reflecting many Stradivarian characteristics, with a flattened arch and more open Fs, and darker, richly textured varnish. The youngest brother, Carlo (1666-1713) also left little trace of his work. But another generation of Rugeri makers carried on, and labels are found up until the 1730s which are the work of Vincenzo's son, Francesco II. The clan was influential and important in Cremona's commercial life, and probably holds more than a few important keys to understanding the real life of the violin maker in the great classical period of lutherie in that city.