Daniel Parker is one of the best and most mysterious makers in the English tradition. His work is pivotal in bringing England into the mainstream of violin making, when previously its reputation had been for the production of viols, widely regarded as the best in the world in the seventeenth century. Prior to 1700, violin makers in England were rare, and those instruments that survive from the period appear odd and even primitive. In fact they were following a well-developed northern European style, different in almost every aspect of technique, construction and aesthetic from the great works of Cremona, by which we now habitually judge everything. But to an instrument maker in England in the seventeenth century, it would have been the Cremonese who appeared odd and outlandish. Only a precious few Amati instruments would have been available to study and imitate.

That situation seems to have changed quite dramatically in the first decade of the eighteenth century, and it seems that Daniel Parker was the first to realise the qualities of the Cremonese, and astonishingly given the date, Stradivari himself. Parker's instruments represent a quantum leap forward in design and construction, and are firmly rooted in Stradivari's work of the period 1690-1700.

How this might have happened is an interesting story. In 1703, a Cremonese violinist, Gaspare Visconti, came to London. His compositions were published there by John Walsh and John Hare, who had connections with the violin trade and Parker himself. In 1704 Visconti married Christina Steffkin, a member of a celebrated family of London musicians. To celebrate the marriage, Visconti seems to have commissioned a cello from Stradivari for his wife, and the original template for the neck of this instrument remains in the Stradivari museum in Cremona, inscribed with her name. It is obvious that Visconti knew Stradivari well, and that the violin he brought with him to London would have been one of his. Through John Hare, for whom he seems to have worked at some time, Parker presumably gained access to the Visconti violin, and very probably made patterns of it, from which came a whole new school of English violins, based on the very latest Stradivari ideas.

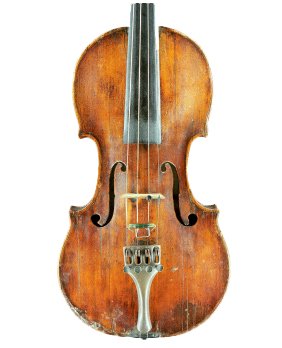

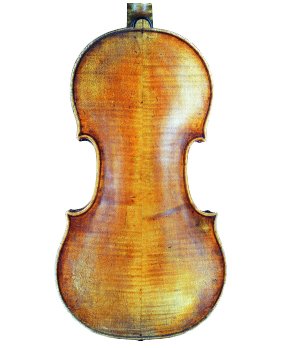

The only problem is that we still don't know who Parker was. It has proved impossible so far to trace his name and origins, partly because the name is so common in parish archives. Very few authentic labels survive, but the instruments in which they appear are most often beautifully made, sturdy and well-varnished models of the 'Long Pattern' Stradivari. Stradivari only made this type for the last ten years of the seventeenth century, but the essential proportions, blackened scroll chamfers and distinctively downward-pointing upper corners are caught accurately in Parker's copies. The arching Parker employed is a little fuller than the originals, but the sound is often outstanding. The finest endorsement of this comes from Fritz Kreisler, who regularly played a Parker violin in preference to his del Gesu. But Parker's work satisfies visually as well; the quality of the red varnish is usually very fine, and seems to derive from the best of the seventeenth century London viol makers. Instruments displaying very similar workmanship are found with the label of John Hare, and later his widow Elizabeth, and this provides the evidence that Parker worked for the Hares, who ran what was essentially a general music shop in Cornhill in the city of London. The Hare-labelled instruments generally have a slightly inferior varnish, of a duller brown colour. More significantly, there are a handful of violins bearing the label of Barak Norman (1651-1724), the celebrated viol maker of the period, which display some of the idiosyncracies of Parker's work, including the strongly tinted but transparent red varnish. It is more than likely that Parker gained some experience in the Norman shop.

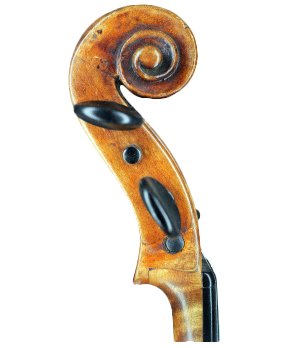

Characteristically, Parker's work is slightly coarse in finish, vigorously carved but very well-shaped. The scrolls are finely balanced in the spiral, round and well-defined, but the turns taper outward slightly. The purfling is a little broad and rope-like- both black and white strips are made of soft, poplar-like wood which shows creases and irregularities in the inlaying. A strikingly inlaid viola by Parker has this typical and distinctive purfling cut into fleur-de-lys forms in the corners. Edges are generally deeply cut and strongly turned. The F holes are generally broad and upright, with distinctively pointed inner corners to the lower wings. In terms of sophistication and refinement Parker's work cannot compete in any way with Stradivari's masterpieces, but they have a sturdy charm which is totally distinctive and completely admirable.

Unfortunately for the English violin trade, Parker's innovative instruments were generally overlooked for the remainder of the eighteenth century. The cult of Stradivari did not take hold, and Stainer became virtually the universal pattern for English violin makers. Other London makers ignored the flatter arching, the broad outline and the brilliant red varnish that Parker used, ahead of his time as it turned out. Stradivari's ideas were not re-established until 1800 in London, and it now seems as if the violin makers of eighteenth century England were generally headed down a blind alley, despite Daniel Parker's clear signalling in the other direction.