Camillus Camilli is a delightful maker. His instruments are blessed with classical style and proportion, and the most charming of scrolls, yet are very distinctive and recognisable. Quite how such a clearly personal style evolved within the very close confines of Cremonese technique and geometry is an interesting question, not easily answered.

To begin with, Camilli was born in Mantua- so it is believed- in about 1704, and worked there all his life. How he came to be possessed of a Cremonese approach is not as obvious as it may seem. Although Mantua is not far distant geographically from the home of violin making, there were certainly makers in nearby Milan or even Piacenza with no obvious debt to Cremona. Peter Guarneri is the obvious link; he moved to Mantua from Cremona in around 1680 as a court musician and instrument maker, bringing with him all the experience of his father Andrea Guarneri's workshop and apprenticeship with Nicolo Amati. Guarneri died in 1720 however, when Camilli was only 16. Old enough to have served an apprenticeship nevertheless, which often began at the age of 13 or even earlier in those days. What is intriguing still is the possible influence of a senior Mantuan maker Antonio Zanotus, who was born in Lodi in about 1690, and claimed to have been a pupil of Hieronymus Amati II. This is not as unlikely as it seems, since we know that Amati left Cremona for Piacenza for several years after 1700, and Lodi is situated close by, between Piacenza and Milan.

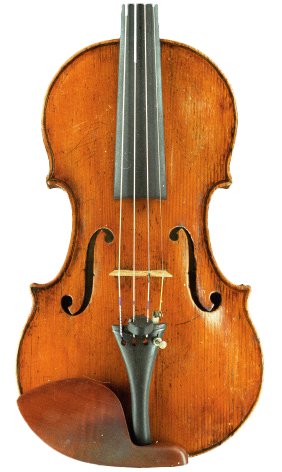

Whatever the course of events, we see in Camilli's work the sure signifiers of Cremonese procedures, the pins in the ends of the plates as well as the central pin in the interior of the back. The linings are morticed into the blocks, evidence of an interior mould being used, and the form of the scroll follows the Amati geometry to perfection. The differences are slight in the exterior form; Camillis tend to be a little broader across the lower corners than most, and the arching can be very full, like some of Peter Guarneri's more exaggerated Stainer models, but without such a marked recurve around the edges. Camilli's model is very consistent, and never departs from an Amati prototype, nor does it acknowledge any influence of Stradivari. The main and most striking difference between Camilli's work and that of his Cremonese contemporaries, which would have to include Stradivari, Bergonzi and del Gesu, is his varnish. It has all the appearance of a soft spirit-resin concoction rather than the very supple oil recipes used in Cremona, and is always within the yellow-gold-orange spectrum. It never takes on the rich golden brown of early Amati nor the deep red of Stradivari and del Gesu, but still has a warmth and depth most modern makers would happily kill for. Interestingly, Camilli's instruments are uniformly varnished under the fingerboard. It is a consistent feature of Cremonese work that the area of the front covered by the board is bare, indicating that the varnish was applied with the fingerboard already in place. This was evidently not Camilli's practice.

Camilli was as good and careful a craftsman as any. His taste and workmanship was first-class, and he seems to have been prolific, although no cellos or violas by him have come to light. With the Cremona varnish, and even perhaps with a more enlightened approach to arching and the advances being made in that direction during his lifetime, he might have entered the pantheon at the highest level. What we have of him however is honest and true, and more than easy on the eye and ear. He died in 1754, having passed on his expertise to his supposed pupil Tomaso Balestrieri, who did eventually honour the debt to Stradivari and del Gesu by building more powerful toned, yet slightly less refined instruments in many ways distant from those of his master.