Antonio Gragnani was one of the most elegant and stylish of eighteenth century Italian makers. Working only shortly after the demise of the greatest makers of Cremona, but almost contemporary with G.B. Guadagnini, Graganani hung onto the principle of fine craftsmanship and high finish while many others declined into hasty and poorly-conceived work in the rapid expansion of lutherie as a profession throughout Europe.

Working from around 1765 until the end of the century in Livorno on the Ligurian coast of Italy, he almost certainly learned his craft in Florence, a mere fifty kilometres eastward. His work has strong elements of Giovanni Baptista Gabrielli and of his contemporaries Lorenzo and Tomasso Carcassi, the dominant Florentine makers of the period. Typically Florentine work has a fine, if slightly glassy varnish, and a strong tang of Stainer in the modelling, the sweep of the soundholes and the tight spiral of the scroll. Stainer was certainly a defining influence at the time, over and above the Cremonese, but Graganani successfully integrated Stradivarian ideas into his designs.

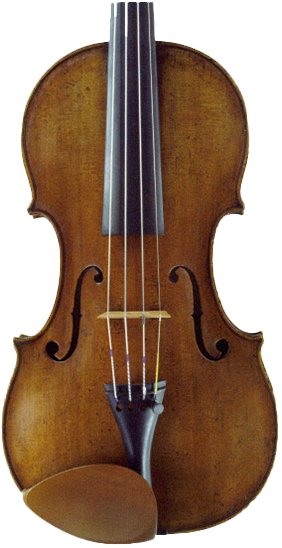

While the Carcassi brothers work became rather slipshod towards the end of the eighteenth century, Gragnani in Livorno retained a firm discipline in all his efforts. Sometimes the arching became a little high and pinched, but always immaculately executed. The dominant sense of his designs is an elongated, almost Modigliani-like elegance, far removed from the well-rounded Stainer form, and possibly influenced by the 'long pattern' of Stradivari, although the instruments themselves are not oversized. While the F's retain a certain Stainer swing to them, they too are elongated and beautifully laid along the smoothly cylindrical arching of the table.

Gragnani generally chose fine timber- close, straight-grained spruce and well flamed maple of conventional cut and appearance, and a golden-yellow varnish, which ages well, but lacks the supple texture of classical Cremonese recipes.

Two- or three- distinctive elements identify Gragnani's work. The most obvious being the idiosyncratic but charming head. The long, swan-necked pegbox is sinuously carved throughout its length, with the sides curving inward toward the top of the pegbox mortice, and the back flared out to a full, deeply fluted width. The chamfers are small and precisely cut, and to accentuate the longitudinal flow of the pegbox, the head has a strong ovality to the spiral. Secondly, Gragnani chose to use whalebone for the black elements of his purfling. As far as I am aware he is unique in Italy in this respect, although it was common practice amongst makers in the Netherlands during the previous century. Whether the port of Livorno had any special access for whaling ships I do not know, and the Mediterranean does not seem a likely hunting ground, but nevertheless whalebone was a widely used material in many crafts, used for its dense, smooth surface and supple, plastic qualities. The polished texture of whalebone is distinctive under low magnification and usually easy to see in the purfling of violins. For the white core, Graganani generally used beechwood, like his Florentine colleagues.

Lastly, Gragnani seemed determined to make his mark as a distinctive and individual maker- so much of his work is conscientiously different, yet always carefully crafted to the highest standards, and he imposed his brand mark conspicuously on almost every part of the instrument. However, the large 'AG' mark turned out not to be a deterrent to fakers and forgers, if that was indeed his intention. As is often the case, the more idiosyncratic a style, the more tempting it is to forgers, who know only too well that experts will quickly seize on such marks as signs of authenticity. Early in their career, the Voller brothers even managed to export Gragnani copies, clearly marked with their own home-made AG brand and fitted out with ebony rather than whalebone purfling, to Florence itself.

At least you can fall back on the most well-worn of cliché- imitation is the sincerest form of flattery- to highlight the fact that Antonio Gragnani's work was valued well enough by 1890, when the Vollers' coup was observed by Alfred Hill, to make forgery profitable. Since then, Graganani's instruments have risen in worth like all the other makers of his quality and provenance. Just beware of instruments bearing brands. It may well be that all the work of an individual maker bears his brand, but not all the branded instruments are necessarily his work.